Do buddhists entertain the idea they mght be delusional abou

-

Originally posted by AndrewPKYap:

Sorry, I don't believe in the supernatural. That is invented by some people to cash in on human failings (propensity to believe in the supernatural without any valid evidence of the supernatural) of some people (actually most people).

So while I might be interested in buddhist philosophy, I have no interest in buddhist superstitions (buddhist beliefs in the supernatural)

I don't mean to imply what you had said is totally irrelevant by not quoting your entire text. My apologies. It's more of a convenience to myself in terms of reading and typing out my comments.

For me, I just put aside whatever I cannot prove or experience as yet, be it Buddhist superstitutions or whatever. My post was not to convince, suggest or impose on anyone to believe in the supernatural or that of Buddhist beliefs in the supernatural.

-

Originally posted by An Eternal Now:

...Hence everything is vivid yet empty and without substance, like a mirage, like a magick trick, like an illusion but NOT an illusion, like a dream but NOT a dream, for there is no other separate reality apart from these shimmering mirage-like display of pure awareness, which does not disappear in enlightenment but can only be correctly perceived.

The above is one of those profound teachings in Buddhism. Like an illusion, but NOT an illusion, and so on.

Pure awareness is displayed in the form of shimmering mirage-like reality?

I wonder how or what I should do if I see someone who's drowning or bleeding, etc. Do I tell myself, it's LIKE he's suffering, but he's NOT actually suffering. He's just appearing to be suffering.

-

Originally posted by Spnw07:

The above is one of those profound teachings in Buddhism. Like an illusion, but NOT an illusion, and so on.

Pure awareness is displayed in the form of shimmering mirage-like reality?

I wonder how or what I should do if I see someone who's drowning or bleeding, etc. Do I tell myself, it's LIKE he's suffering, but he's NOT actually suffering. He's just appearing to be suffering.

Yes, everything is a vivid appearance of pure awareness. Like the words on this screen is an appearance. It is appearing. His suffering is appearing. Precisely because it is appearing that steps should be taken to deal with those appearance. If suffering is not appearing, then why would you do anything about it? So compassion arises naturally in regards to appearances.

The only problem is when we imagine that behind those appearances there is an inherently existing thing or a self, or that there is an inherently existing 'self' that is acting to save 'other' beings. There is action, but there is no doer and no one being saved. In reality there is just dependently originated appearances, nothing graspable or inherent. In fact there would be no suffering if we realise the empty nature of reality. It is only because we are not aware of it, that we fall into a dream state of samsara full of sufferings. Physical pain is inevitable (it is a dependently originated empty yet vivid appearance), but mental suffering as a result of imagining a 'me' suffering is due to not realising emptiness. That is why bodhisattvas have compassion for those suffering beings still asleep, if we were awake and not suffering, there would be no more appearance of Buddhas.

In short: Hence it is not true that there is a 'self' experiencing suffering, but it is true that due to not realising there is no self, that suffering is happening. Yes, there is no sufferer apart from suffering, but the fact is that suffering is still appearing and thus there is compassion for these beings and action is being done to address these issues.

Yes, suffering itself is impermanent, insubstantial, and empty, but due to ignorance of sentient beings and not realising that it is empty, they continue to grasp and suffer due to ignorance. Therefore the Bodhisattvas vow to save them from suffering.

-

http://www.drba.org/dharma/vajrasutra.asp

TRANSFORMING WITHOUT THERE BEING ANYONE TRANSFORMED, TWENTY-FIVE

" Subhuti, what do you think? None of you should maintain that the Thus Come One has this thought: 'I shall save living beings.' Subhuti, do not think that way. Why? In fact the Thus Come One does not save any living beings. If the Thus Come One saved living beings, then the Thus Come One would have a sense of a self, others, living beings, and a life. "Subhuti, although the Thus Come One speaks of the existence of a self, there is really no self that exists. However, common people think they have a self. Subhuti, the common people that the Thus Come One speaks of are not common people. Therefore they are called common people." -

happy new year to all

interesting discussion in this thread. so just add my one cent's worth.

the teachings are open to many intepretations, and depending on the conditions a practitioner is living with (both internal and external conditions), degree of understanding and realization along the way will differ.

some of these teachings can actually be (or has been) investigated using modern scientific methods.

an interesting video i would like to share with all

http://www.ted.com/talks/vilayanur_ramachandran_on_your_mind.html

yes delusions are part and parcel of this life, and will continue to be until one is awaken. and when we think we are awakened it is probably not so.

-

ULTIMATELY THERE IS NO SELF, SEVENTEEN

Then Subhuti addressed the Buddha, "World Honored One, if a good man or good woman resolves his mind on Anuttarasamyaksambodhi, on what should he rely? How should he subdue his mind?" The Buddha told Subhuti, "A good man or good woman who resolves his mind on Anuttarasamyaksambodhi should think thus: 'I should take all living beings across to Cessation. Yet when all living beings have been taken across to Cessation, actually not one living being has been taken across to Cessation.' Why? Subhuti, if a Bodhisattva has an appearance of self, others, living beings or a life, he is not a Bodhisattva. -

Life is an illusion and it is simulated by a computer of a more advanced world/

-

Originally posted by AndrewPKYap:

Sorry, I don't believe in the supernatural. That is invented by some people to cash in on human failings (propensity to believe in the supernatural without any valid evidence of the supernatural) of some people (actually most people).

So while I might be interested in buddhist philosophy, I have no interest in buddhist superstitions (buddhist beliefs in the supernatural)

what is considered supernatural (in a general context) is constantly changing as society and technoglogy progresses through the ages. an eclipse used to be a supernatural occurence in olden days, as chinese named the phenomenon 天狗食日 (celestial dog devouring the sun), but later scientific discoveries proofed othewise. while the natural functioning of the phenomenon remains unchanged, the label we humans give it changes depending on our conceptual understanding of it - supernatural for things we can't yet explain or understand, and science for the same thing that later generations did get their conceptual brains around it. but in the end, the natural phenomenon itself still functions as it has always been, regardless of the label that humans gave it.

who knows what science will go on to discover in the coming generations, after all us passionate forummers here had long turned to dust :-) perhaps by then, what is considered supernatural now will be just primary school science topics by then.

-

Originally posted by Larryteo:

Life is an illusion and it is simulated by a computer of a more advanced world/

You watch too much Matrix

-

Originally posted by An Eternal Now:

You watch too much Matrix

I have this feeling one day i will wake up and someone will tell me my life is digital. After that I will cry and cry for days and die.

-

Originally posted by Jamber:

what is considered supernatural (in a general context) is constantly changing as society and technoglogy progresses through the ages. an eclipse used to be a supernatural occurence in olden days, as chinese named the phenomenon 天狗食日 (celestial dog devouring the sun), but later scientific discoveries proofed othewise. while the natural functioning of the phenomenon remains unchanged, the label we humans give it changes depending on our conceptual understanding of it - supernatural for things we can't yet explain or understand, and science for the same thing that later generations did get their conceptual brains around it. but in the end, the natural phenomenon itself still functions as it has always been, regardless of the label that humans gave it.

who knows what science will go on to discover in the coming generations, after all us passionate forummers here had long turned to dust :-) perhaps by then, what is considered supernatural now will be just primary school science topics by then.

Ah, good realistic example there, by quoting the eclipse. Indeed the label we humans give to things or phenomena we can't explain or understand changes depending on our conceptual understanding at any point in time.

"...in the end, the natural phenomenon itself still functions as it has always been, regardless of the label that humans gave it."

Totally agree. :)

-

Originally posted by Spnw07:

I wonder how or what I should do if I see someone who's drowning or bleeding, etc. Do I tell myself, it's LIKE he's suffering, but he's NOT actually suffering. He's just appearing to be suffering.

imagine you are a character in an action movie, and you see someone who's drowning or bleeding, and if you don't do anything, the person will naturally die as a result. if you save the person, he/she will not die as a result of your action. all laws of karma will still function as usual in the movie.

but if you change your perspective and realize that all these happenings is nothing but a movie, it appears like an illusion (since movie is not real-life). but nevertheless, characters in the movie still goes through sufferings, happiness, lives and dies, as a consequence of how the plot unfolds, and all laws of nature and karma will still be very real from the movie's content perspective.

this is just an analogy for purpose of providing a quick response to your question. don't take it too literally and over-analyse :-)

-

Originally posted by Jamber:

what is considered supernatural (in a general context) is constantly changing as society and technoglogy progresses through the ages. an eclipse used to be a supernatural occurence in olden days, as chinese named the phenomenon 天狗食日 (celestial dog devouring the sun), but later scientific discoveries proofed othewise. while the natural functioning of the phenomenon remains unchanged, the label we humans give it changes depending on our conceptual understanding of it - supernatural for things we can't yet explain or understand, and science for the same thing that later generations did get their conceptual brains around it. but in the end, the natural phenomenon itself still functions as it has always been, regardless of the label that humans gave it.

who knows what science will go on to discover in the coming generations, after all us passionate forummers here had long turned to dust :-) perhaps by then, what is considered supernatural now will be just primary school science topics by then.

For those more intellectual type of persons, the following article is a very good read IMO and explains why the empty nature of universe allows so called non-local and supernatural occurences. This is also the experience of Thusness and he has said how supernatural experience but he prefers to call it non-local events (e.g. hear not bounded by distance, see not bounded by distance, read other's minds and see into the future, etc) that take places will help deepen one's insight of emptiness. (But only for a person at that level of spiritual maturity and wisdom to comprehend it, otherwise people who attain supernatural powers at an early phase in one's practice can get over fascinated and attached to them and fail to give rise to wisdom, that's why he is always reluctant to discuss these things)

The Holographic Universe

Michael Talbot

In 1982 a remarkable event took place. At the University of Paris a research team led by physicist Alain Aspect performed what may turn out to be one of the most important experiments of the 20th century. You did not hear about it on the evening news. In fact, unless you are in the habit of reading scientific journals you probably have never even heard Aspect's name, though there are some who believe his discovery may change the face of science.

Aspect and his team discovered that under certain circumstances subatomic particles such as electrons are able to instantaneously communicate with each other regardless of the distance separating them. It doesn't matter whether they are 10 feet or 10 billion miles apart.

Somehow each particle always seems to know what the other is doing. The problem with this feat is that it violates Einstein's long-held tenet that no communication can travel faster than the speed of light. Since traveling faster than the speed of light is tantamount to breaking the time barrier, this daunting prospect has caused some physicists to try to come up with elaborate ways to explain away Aspect's findings. But it has inspired others to offer even more radical explanations.

University of London physicist David Bohm, for example, believes Aspect's findings imply that objective reality does not exist, that despite its apparent solidity the universe is at heart a phantasm, a gigantic and splendidly detailed hologram.

To understand why Bohm makes this startling assertion, one must first understand a little about holograms. A hologram is a three- dimensional photograph made with the aid of a laser.

To make a hologram, the object to be photographed is first bathed in the light of a laser beam. Then a second laser beam is bounced off the reflected light of the first and the resulting interference pattern (the area where the two laser beams commingle) is captured on film.

When the film is developed, it looks like a meaningless swirl of light and dark lines. But as soon as the developed film is illuminated by another laser beam, a three-dimensional image of the original object appears.

The three-dimensionality of such images is not the only remarkable characteristic of holograms. If a hologram of a rose is cut in half and then illuminated by a laser, each half will still be found to contain the entire image of the rose.

Indeed, even if the halves are divided again, each snippet of film will always be found to contain a smaller but intact version of the original image. Unlike normal photographs, every part of a hologram contains all the information possessed by the whole.

The "whole in every part" nature of a hologram provides us with an entirely new way of understanding organization and order. For most of its history, Western science has labored under the bias that the best way to understand a physical phenomenon, whether a frog or an atom, is to dissect it and study its respective parts.

A hologram teaches us that some things in the universe may not lend themselves to this approach. If we try to take apart something constructed holographically, we will not get the pieces of which it is made, we will only get smaller wholes.

This insight suggested to Bohm another way of understanding Aspect's discovery. Bohm believes the reason subatomic particles are able to remain in contact with one another regardless of the distance separating them is not because they are sending some sort of mysterious signal back and forth, but because their separateness is an illusion. He argues that at some deeper level of reality such particles are not individual entities, but are actually extensions of the same fundamental something.

To enable people to better visualize what he means, Bohm offers the following illustration.

Imagine an aquarium containing a fish. Imagine also that you are unable to see the aquarium directly and your knowledge about it and what it contains comes from two television cameras, one directed at the aquarium's front and the other directed at its side.

As you stare at the two television monitors, you might assume that the fish on each of the screens are separate entities. After all, because the cameras are set at different angles, each of the images will be slightly different. But as you continue to watch the two fish, you will eventually become aware that there is a certain relationship between them.

When one turns, the other also makes a slightly different but corresponding turn; when one faces the front, the other always faces toward the side. If you remain unaware of the full scope of the situation, you might even conclude that the fish must be instantaneously communicating with one another, but this is clearly not the case.

This, says Bohm, is precisely what is going on between the subatomic particles in Aspect's experiment.

According to Bohm, the apparent faster-than-light connection between subatomic particles is really telling us that there is a deeper level of reality we are not privy to, a more complex dimension beyond our own that is analogous to the aquarium. And, he adds, we view objects such as subatomic particles as separate from one another because we are seeing only a portion of their reality.

Such particles are not separate "parts", but facets of a deeper and more underlying unity that is ultimately as holographic and indivisible as the previously mentioned rose. And since everything in physical reality is comprised of these "eidolons", the universe is itself a projection, a hologram.

In addition to its phantomlike nature, such a universe would possess other rather startling features. If the apparent separateness of subatomic particles is illusory, it means that at a deeper level of reality all things in the universe are infinitely interconnected.

The electrons in a carbon atom in the human brain are connected to the subatomic particles that comprise every salmon that swims, every heart that beats, and every star that shimmers in the sky.

Everything interpenetrates everything, and although human nature may seek to categorize and pigeonhole and subdivide, the various phenomena of the universe, all apportionments are of necessity artificial and all of nature is ultimately a seamless web.

In a holographic universe, even time and space could no longer be viewed as fundamentals. Because concepts such as location break down in a universe in which nothing is truly separate from anything else, time and three-dimensional space, like the images of the fish on the TV monitors, would also have to be viewed as projections of this deeper order.

At its deeper level reality is a sort of superhologram in which the past, present, and future all exist simultaneously. This suggests that given the proper tools it might even be possible to someday reach into the superholographic level of reality and pluck out scenes from the long-forgotten past.

What else the superhologram contains is an open-ended question. Allowing, for the sake of argument, that the superhologram is the matrix that has given birth to everything in our universe, at the very least it contains every subatomic particle that has been or will be -- every configuration of matter and energy that is possible, from snowflakes to quasars, from bluü whales to gamma rays. It must be seen as a sort of cosmic storehouse of "All That Is."

Although Bohm concedes that we have no way of knowing what else might lie hidden in the superhologram, he does venture to say that we have no reason to assume it does not contain more. Or as he puts it, perhaps the superholographic level of reality is a "mere stage" beyond which lies "an infinity of further development".

Bohm is not the only researcher who has found evidence that the universe is a hologram. Working independently in the field of brain research, Standford neurophysiologist Karl Pribram has also become persuaded of the holographic nature of reality.

Pribram was drawn to the holographic model by the puzzle of how and where memories are stored in the brain. For decades numerous studies have shown that rather than being confined to a specific location, memories are dispersed throughout the brain.

In a series of landmark experiments in the 1920s, brain scientist Karl Lashley found that no matter what portion of a rat's brain he removed he was unable to eradicate its memory of how to perform complex tasks it had learned prior to surgery. The only problem was that no one was able to come up with a mechanism that might explain this curious "whole in every part" nature of memory storage.

Then in the 1960s Pribram encountered the concept of holography and realized he had found the explanation brain scientists had been looking for. Pribram believes memories are encoded not in neurons, or small groupings of neurons, but in patterns of nerve impulses that crisscross the entire brain in the same way that patterns of laser light interference crisscross the entire area of a piece of film containing a holographic image. In other words, Pribram believes the brain is itself a hologram.

Pribram's theory also explains how the human brain can store so many memories in so little space. It has been estimated that the human brain has the capacity to memorize something on the order of 10 billion bits of information during the average human lifetime (or roughly the same amount of information contained in five sets of the Encyclopaedia Britannica).

Similarly, it has been discovered that in addition to their other capabilities, holograms possess an astounding capacity for information storage--simply by changing the angle at which the two lasers strike a piece of photographic film, it is possible to record many different images on the same surface. It has been demonstrated that one cubic centimeter of film can hold as many as 10 billion bits of information.

Our uncanny ability to quickly retrieve whatever information we need from the enormous store of our memories becomes more understandable if the brain functions according to holographic principles. If a friend asks you to tell him what comes to mind when he says the word "zebra", you do not have to clumsily sort back through ome gigantic and cerebral alphabetic file to arrive at an answer. Instead, associations like "striped", "horselike", and "animal native to Africa" all pop into your head instantly.

Indeed, one of the most amazing things about the human thinking process is that every piece of information seems instantly cross- correlated with every other piece of information--another feature intrinsic to the hologram. Because every portion of a hologram is infinitely interconnected with ever other portion, it is perhaps nature's supreme example of a cross-correlated system.

The storage of memory is not the only neurophysiological puzzle that becomes more tractable in light of Pribram's holographic model of the brain. Another is how the brain is able to translate the avalanche of frequencies it receives via the senses (light frequencies, sound frequencies, and so on) into the concrete world of our perceptions. Encoding and decoding frequencies is precisely what a hologram does best. Just as a hologram functions as a sort of lens, a translating device able to convert an apparently meaningless blur of frequencies into a coherent image, Pribram believes the brain also comprises a lens and uses holographic principles to mathematically convert the frequencies it receives through he senses into the inner world of our perceptions.

An impressive body of evidence suggests that the brain uses holographic principles to perform its operations. Pribram's theory, in fact, has gained increasing support among neurophysiologists.

Argentinian-Italian researcher Hugo Zucarelli recently extended the holographic model into the world of acoustic phenomena. Puzzled by the fact that humans can locate the source of sounds without moving their heads, even if they only possess hearing in one ear, Zucarelli discovered that holographic principles can explain this ability.

Zucarelli has also developed the technology of holophonic sound, a recording technique able to reproduce acoustic situations with an almost uncanny realism.

Pribram's belief that our brains mathematically construct "hard" reality by relying on input from a frequency domain has also received a good deal of experimental support.

It has been found that each of our senses is sensitive to a much broader range of frequencies than was previously suspected.

Researchers have discovered, for instance, that our visual systems are sensitive to sound frequencies, that our sense of smell is in part dependent on what are now called "osmic frequencies", and that even the cells in our bodies are sensitive to a broad range of frequencies. Such findings suggest that it is only in the holographic domain of consciousness that such frequencies are sorted out and divided up into conventional perceptions.

But the most mind-boggling aspect of Pribram's holographic model of the brain is what happens when it is put together with Bohm's theory. For if the concreteness of the world is but a secondary reality and what is "there" is actually a holographic blur of frequencies, and if the brain is also a hologram and only selects some of the frequencies out of this blur and mathematically transforms them into sensory perceptions, what becomes of objective reality?

Put quite simply, it ceases to exist. As the religions of the East have long upheld, the material world is Maya, an illusion, and although we may think we are physical beings moving through a physical world, this too is an illusion.

We are really "receivers" floating through a kaleidoscopic sea of frequency, and what we extract from this sea and transmogrify into physical reality is but one channel from many extracted out of the superhologram.

This striking new picture of reality, the synthesis of Bohm and Pribram's views, has come to be called the holographic paradigm, and although many scientists have greeted it with skepticism, it has galvanized others. A small but growing group of researchers believe it may be the most accurate model of reality science has arrived at thus far. More than that, some believe it may solve some mysteries that have never before been explainable by science and even establish the paranormal as a part of nature.

Numerous researchers, including Bohm and Pribram, have noted that many para-psychological phenomena become much more understandable in terms of the holographic paradigm.

In a universe in which individual brains are actually indivisible portions of the greater hologram and everything is infinitely interconnected, telepathy may merely be the accessing of the holographic level.

It is obviously much easier to understand how information can travel from the mind of individual 'A' to that of individual 'B' at a far distance point and helps to understand a number of unsolved puzzles in psychology. In particular, Grof feels the holographic paradigm offers a model for understanding many of the baffling phenomena experienced by individuals during altered states of consciousness.

-----------

Also related to the article above:

The metaphor of Indra's Jeweled Net is attributed to an ancient Buddhist named Tu-Shun (557-640 B.C.E.) who asks us to envision a vast net that:

* at each juncture there lies a jewel;

* each jewel reflects all the other jewels in this cosmic matrix.

* Every jewel represents an individual life form, atom, cell or unit of consciousness.

* Each jewel, in turn, is intrinsically and intimately connected to all the others;

* thus, a change in one gem is reflected in all the others.

This last aspect of the jeweled net is explored in a question/answer dialog of teacher and student in the Avatamsaka Sutra. In answer to the question: "how can all these jewels be considered one jewel?" it is replied: "If you don't believe that one jewel...is all the jewels...just put a dot on the jewel [in question]. When one jewel is dotted, there are dots on all the jewels...Since there are dots on all the jewels...We know that all the jewels are one jewel" ...".

The moral of Indra's net is that the compassionate and the constructive interventions a person makes or does can produce a ripple effect of beneficial action that will reverberate throughout the universe or until it plays out. By the same token you cannot damage one strand of the web without damaging the others or setting off a cascade effect of destruction.

Source: Awakening 101

...One of the images used to illustrate the nature of reality as understood in Mahayana is The Jewel Net of Indra. According to this image, all reality is to be understood on analogy with Indra's Net. This net consists entirely of jewels. Each jewel reflects all of the other jewels, and the existence of each jewel is wholly dependent on its reflection in all of the other jewels. As such, all parts of reality are interdependent with each other, but even the most basic parts of existence have no independent existence themselves. As such, to the degree that reality takes form and appears to us, it is because the whole arises in an interdependent matrix of parts to whole and of subject to object. But in the end, there is nothing (literally no-thing) there to grasp....

Source: Sunyata ('Emptiness')

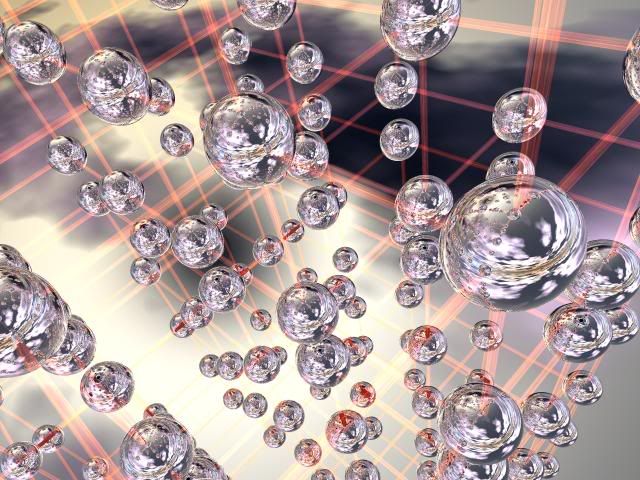

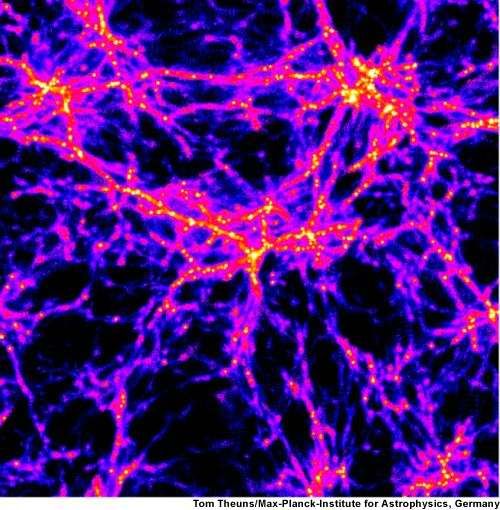

Compare the first picture with:

Computer model of early universe. Gravity arranges matter in thin filaments.

Source: Awakening 101. -

Another related youtube video on non-locality and emptiness:

Non-Locality and Teleportation

Here's a video that Thusness and I found very interesting. I think what is said in this video lines up well with the Buddhist teaching of Emptiness.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wb1u9zOPwiQ&feature=player_embedded

It also reminds me of an article written by Longchen:

The non-solidity of existence

This article describes a spiritual insight. It may be quite hard to understand.

The things that we experience are registered by all the sense organs. The eye sight registers vision, the ears register sound, the body registers sensations. These perception, sensations and experiences are not happening in some places. They are the experience of the arising of certain conditions. There is no solidity and physicality in the actual experience.

What we experienced is not universal and common to all. Here's an example to illustrate that: We know that as human beings, we see in term of colours. Some animals are however colour-blind, thus they see differently from us. But none of us, is really seeing the truth nature directly. The senses of different species of sentient beings experience things differently. So who is seeing the real image of an object? None.

Likewise, the various planes of existence are due to different conditions arising. In certain types of meditation, one is said to be able to access these planes of existence. This is because they are not specific locations. They are mental states and are thus non-localised. In these meditations, our consciousness changes and 'aligned' more with these other states or planes of existence.

All the planes of existence are simultaneously manifesting, but because our senses are human-based conditioned arisings, we only see the human world and other beings that shared 'similar' resonating arising conditions. But nevertheless, the other planes of existences are not elsewhere in some other places.

What we think of as places are really just consciousness and there is no solidity whatsoever. Even our touch sense is just that. The touch sense gives an impression of feeling something that is physical and three-dimensional. But there is really no solid self-existing object there. Instead, it is simply the sensation that gives the impression of physical solidity and form.

OK, that all I can think of and write about this topic. I will revise and improve this article where the need arises.

For your necessary ponderance. Thank you for reading.

These articles are parts of a series of spiritual realisation articles . -

Originally posted by An Eternal Now:

Yes, everything is a vivid appearance of pure awareness. Like the words on this screen is an appearance. It is appearing. His suffering is appearing. Precisely because it is appearing that steps should be taken to deal with those appearance. If suffering is not appearing, then why would you do anything about it? So compassion arises naturally in regards to appearances.

Compassion arises naturally in regards to appearances? Why? If appearances of suffering are like illusions, then they will also disappear like illusions without our intervention or regardless of how we feel.

Do we bother to save the morning dew that gets evaporated when the sun comes out?

Do we bother to save the zebra we see getting chased by a lion?

The only problem is when we imagine that behind those appearances there is an inherently existing thing or a self, or that there is an inherently existing 'self' that is acting to save 'other' beings. There is action, but there is no doer and no one being saved. In reality there is just dependently originated appearances, nothing graspable or inherent. In fact there would be no suffering if we realise the empty nature of reality. It is only because we are not aware of it, that we fall into a dream state of samsara full of sufferings. Physical pain is inevitable (it is a dependently originated empty yet vivid appearance), but mental suffering as a result of imagining a 'me' suffering is due to not realising emptiness. That is why bodhisattvas have compassion for those suffering beings still asleep, if we were awake and not suffering, there would be no more appearance of Buddhas.

In short: Hence it is not true that there is a 'self' experiencing suffering, but it is true that due to not realising there is no self, that suffering is happening. Yes, there is no sufferer apart from suffering, but the fact is that suffering is still appearing and thus there is compassion for these beings and action is being done to address these issues.

Yes, suffering itself is impermanent, insubstantial, and empty, but due to ignorance of sentient beings and not realising that it is empty, they continue to grasp and suffer due to ignorance. Therefore the Bodhisattvas vow to save them from suffering.

Physical and mental pain or discomfort are two separate things? I thought they are inter-connected.

Is having a headache or migraine something physical or mental? There are no specific external body parts involved.

When I'm hungry, I feel weak. Is that physical or mental? Can I wish or will away hunger? When I am having a fever, I feel hot and uncomfortable. When I am diagnosed with kidney failure and undergo daily dialysis (which is freaking uncomfortable), can I wish or will away sickness?

If there is no sufferer apart from suffering, why do Bodhisattvas need to have compassion for beings? There should be NO beings to feel or develop compassion for, isn't it?

If suffering is impermanent, insubstantial, and empty, then is compassion impermanent, insubstantial and empty too?

-

As I said, life is an illusion and it is simulated by a computer, how many times do you want me to repeat???????

-

Originally posted by Jamber:

imagine you are a character in an action movie, and you see someone who's drowning or bleeding, and if you don't do anything, the person will naturally die as a result. if you save the person, he/she will not die as a result of your action. all laws of karma will still function as usual in the movie.

but if you change your perspective and realize that all these happenings is nothing but a movie, it appears like an illusion (since movie is not real-life). but nevertheless, characters in the movie still goes through sufferings, happiness, lives and dies, as a consequence of how the plot unfolds, and all laws of nature and karma will still be very real from the movie's content perspective.

this is just an analogy for purpose of providing a quick response to your question. don't take it too literally and over-analyse :-)

Maybe you can substitute the word 'character' with 'actor'. If I'm an actor acting out an character who looks at another co-actor acting out a drowning character, I won't be so foolish as to be anxious to save him or her, unless it's part of the script. Safety procedures will definitely be in place (maybe divers are supporting that co-actor under the sea surface). This will also be the same if I'm acting out the drowning character.

If the setting is a mere swimming pool but merely flimed in such a way to appear like the sea, there's little need to raise a real alarm of danger, isn't it?

Anyway, this is just sharing my thoughts. Don't take it too literally and over-analyse too. =)

-

Compassion arises naturally in regards to appearances? Why? If appearances of suffering are like illusions, then they will also disappear like illusions without our intervention or regardless of how we feel.

Do we bother to save the morning dew that gets evaporated when the sun comes out?

Do we bother to save the zebra we see getting chased by a lion?

As I explained to AndrewPKYap, there is a big difference between 'the world is an illusion' and 'the world is LIKE an illusion'. And because the world is not an illusion, it cannot disappear (though the mental suffering arising due to ignorance can disappear). While non-Buddhist teachings preach the prior, Buddhism teaches the latter. What's the difference?

From my post to AndrewPKYap:

Actually it is not that the world is literally an illusion, but LIKE an illusion... there's an important difference between these two and although it might be a little off topic, I thought it is important to clarify the Buddhist view, and distinguish it from other non-Buddhist teachings.

The following excerpts is from a very enlightened yogi and teacher (he had attended more than a decade of meditation retreat and was given the titled 'Mahayogi Rinpoche' by his guru) and I have posted it in my blog on Thusness's suggestion. Anyone who still holds an ultimate reality to be real hasn't pass beyond Stage 4 of Thusness/PasserBy's Seven Stages of Enlightenment

Madhyamika Buddhism Vis-a-vis Hindu Vedanta

...So in the Buddhist paradigm, it is not only not necessary to have an eternal ground for liberation, but in fact the belief in such a ground itself is part of the dynamics of ignorance. We move here to another to major difference within the two paradigms. In Hinduism liberation occurs when this illusory Samsara is completely relinquished and it vanishes; what remains is the eternal Brahma, which is the same as liberation. Since the thesis is that Samsara is merely an illusion, when it vanishes through knowledge, if there were no eternal Brahma remaining, it would be a disaster. So in the Hindu paradigm (or according to Buddhism all paradigms based on ignorance), an eternal unchanging, independent, really existing substratum (Skt. mahavastu) is a necessity for liberation, else one would fall into nihilism. But since the Buddhist paradigm is totally different, the question posed by Hindu scholars: “How can there be liberation if a Brahma does not remain after the illusory Samsara vanishes in Gyana?” is a non question with no relevance in the Buddhist paradigm and its Enlightenment or Nirvana.

First of all, to the Buddha and Nagarjuna, Samsara is not an illusion but like an illusion. There is a quantum leap in the meaning of these two statements. Secondly, because it is only ‘like an illusion’ i.e. interdependently arisen like all illusions, it does not and cannot vanish, so Nirvana is not when Samsara vanishes like mist and the Brahma arises like the sun out of the mist but rather when seeing that the true nature of Samsara is itself Nirvana. So whereas Brahma and Samsara are two different entities, one real and the other unreal, one existing and the other non-existing, Samsara and Nirvana in Buddhism are one and not two. Nirvana is the nature of Samsara or in Nagarjuna’s words shunyata is the nature of Samsara. It is the realization of the nature of Samsara as empty which cuts at the very root of ignorance and results in knowledge not of another thing beyond Samsara but of the way Samsara itself actually exists (Skt. vastusthiti), knowledge of Tathata (as it-is-ness) the Yathabhuta (as it really is) of Samsara itself. It is this knowledge that liberates from wrong conceptual experience of Samsara to the unconditioned experience of Samsara itself. That is what is meant by the indivisibility of Samsara and Nirvana (Skt. Samsara nirvana abhinnata, Tib: Khor de yer me). The mind being Samsara in the context of DzogChen, Mahamudra and Anuttara Tantra. Samsara would be substituted by dualistic mind. The Hindu paradigm is world denying, affirming the Brahma. The Buddhist paradigm does not deny the world; it only rectifies our wrong vision (Skt. mithya drsti) of the world. It does not give a dream beyond or separate transcendence from Samsara. Because such a dream is part of the dynamics of ignorance, to present such a dream would be only to perpetuate ignorance.

To Buddhism, any system or paradigm which propagates such an unproven and improvable dream as an eternal substance or ultimate reality, be it Hinduism or any other ‘ism’, is propagating spiritual materialism and not true spirituality. To Hinduism such a Brahma is the summum bonum of its search goal, the peak of the Hindu thesis. The Hindu paradigm would collapse without it. Since Buddhism denies thus, it cannot be said honestly that the Buddha merely meant to reform Hinduism. As I have said, it is a totally different paradigm. Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Jainism are all variations of the same paradigm. So truly speaking, you could speak of them as reformations of each other. But Buddhism has a totally different paradigm from any of these, not merely from Vedic- Hinduism...Physical and mental pain or discomfort are two separate things? I thought they are inter-connected.

Is having a headache or migraine something physical or mental? There are no specific external body parts involved.

When I'm hungry, I feel weak. Is that physical or mental? Can I wish or will away hunger? When I am having a fever, I feel hot and uncomfortable. When I am diagnosed with kidney failure and undergo daily dialysis (which is freaking uncomfortable), can I wish or will away sickness?

If there is no sufferer apart from suffering, why do Bodhisattvas need to have compassion for beings? There should be NO beings to feel or develop compassion for, isn't it?

If suffering is impermanent, insubstantial, and empty, then is compassion impermanent, insubstantial and empty too?

You have an extreme view of non-existence: that the world is non-existent, an illusion. However in Buddhism we do not teach that the world is an illusion, as explained above. Whereas in Buddhism we do not deny the reality of pain, the reality of world, but that the world is empty of inherent, independent existence. It is ungraspable but clearly presence-ing, appearing, as the most clear and vivid Presence itself. If you realise this Presence you cannot deny this because it is the luminosity of Buddha-Nature itself which is so clear, more real than real that you cannot have a doubt about it. There is no separation between you and what is perceived, so there is just THAT - the vividness of sound, the pain, the scenery. Yet when we try to locate it, and find an independent inherent existence of say a person, a self, or the 'redness' of a red flower, it cannot be found anywhere we look. It is just appearing but without substance, however this does not deny the presence, appearance, reality of the pain/suffering/etc.

Compassion is a natural response to perceiving someone elses pain. Because pain is arising and it is not an illusion -- it is the experiential reality of the other person, and action can be done to help the other person relatively speaking, but at the same time there is no need for an illusion that there is 'someone suffering' or 'someone who can save the person suffering'. There are just experiences without experiencer, action without doer, and all experiences are vivid but empty.

Yes, physical pain and suffering can be separated. I cannot say I am at that level, so I can quote something from a highly experienced monk Bhante Gunaratana to give you an idea:

http://www.vipassana.com/meditation/mindfulness_in_plain_english_12.php

That last part is more subtle. There are really no human words to describe this action precisely. The best way to get a handle on it is by analogy. Examine what you did to those tight muscles and transfer that same action over to the mental sphere; relax the mind in the same way that you relax the body. Buddhism recognizes that the body and mind are tightly linked. This is so true that many people will not see this as a two-step procedure. For them to relax the body is to relax the mind and vice versa. These people will experience the entire relaxation, mental and physical, as a single process. In any case, just let go completely till you awareness slows down past that barrier which you yourself erected. It was a gap, a sense of distance between self and others. It was a borderline between 'me' and 'the pain'. Dissolve that barrier, and separation vanishes. You slow down into that sea of surging sensation and you merge with the pain. You become the pain. You watch its ebb and flow and something surprising happens. It no longer hurts. Suffering is gone. Only the pain remains, an experience, nothing more. The 'me' who was being hurt has gone. The result is freedom from pain.

This is an incremental process. In the beginning, you can expect to succeed with small pains and be defeated by big ones. Like most of our skills, it grows with practice. The more you practice, the bigger the pain you can handle. Please understand fully. There is no masochism being advocated here. Self-mortification is not the point.

-

Actually it is not that the world is literally an illusion, but LIKE an illusion... there's an important difference between these two and although it might be a little off topic, I thought it is important to clarify the Buddhist view, and distinguish it from other non-Buddhist teachings.

The following excerpts is from a very enlightened yogi and teacher (he had attended more than a decade of meditation retreat and was given the titled 'Mahayogi Rinpoche' by his guru) and I have posted it in my blog on Thusness's suggestion. Anyone who still holds an ultimate reality to be real hasn't pass beyond Stage 4 of Thusness/PasserBy's Seven Stages of Enlightenment

Madhyamika Buddhism Vis-a-vis Hindu Vedanta

First of all, to the Buddha and Nagarjuna, Samsara is not an illusion but like an illusion. There is a quantum leap in the meaning of these two statements. Secondly, because it is only ‘like an illusion’ i.e. interdependently arisen like all illusions, it does not and cannot vanish, so Nirvana is not when Samsara vanishes like mist and the Brahma arises like the sun out of the mist but rather when seeing that the true nature of Samsara is itself Nirvana.So whereas Brahma and Samsara are two different entities, one real and the other unreal, one existing and the other non-existing, Samsara and Nirvana in Buddhism are one and not two. Nirvana is the nature of Samsara or in Nagarjuna’s words shunyata is the nature of Samsara. It is the realization of the nature of Samsara as empty which cuts at the very root of ignorance and results in knowledge not of another thing beyond Samsara but of the way Samsara itself actually exists (Skt. vastusthiti), knowledge of Tathata (as it-is-ness) the Yathabhuta (as it really is) of Samsara itself. It is this knowledge that liberates from wrong conceptual experience of Samsara to the unconditioned experience of Samsara itself. That is what is meant by the indivisibility of Samsara and Nirvana (Skt. Samsara nirvana abhinnata, Tib: Khor de yer me). The mind being Samsara in the context of DzogChen, Mahamudra and Anuttara Tantra. Samsara would be substituted by dualistic mind. The Hindu paradigm is world denying, affirming the Brahma. The Buddhist paradigm does not deny the world; it only rectifies our wrong vision (Skt. mithya drsti) of the world. It does not give a dream beyond or separate transcendence from Samsara. Because such a dream is part of the dynamics of ignorance, to present such a dream would be only to perpetuate ignorance.

To Buddhism, any system or paradigm which propagates such an unproven and improvable dream as an eternal substance or ultimate reality, be it Hinduism or any other ‘ism’, is propagating spiritual materialism and not true spirituality. To Hinduism such a Brahma is the summum bonum of its search goal, the peak of the Hindu thesis. The Hindu paradigm would collapse without it. Since Buddhism denies thus, it cannot be said honestly that the Buddha merely meant to reform Hinduism. As I have said, it is a totally different paradigm. Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Jainism are all variations of the same paradigm. So truly speaking, you could speak of them as reformations of each other. But Buddhism has a totally different paradigm from any of these, not merely from Vedic- Hinduism...Is the true nature of Nirvana Samsara as well since it is one and not two?

You have an extreme view of non-existence: that the world is non-existent, an illusion. However in Buddhism we do not teach that the world is an illusion, as explained above. Whereas in Buddhism we do not deny the reality of pain, the reality of world, but that the world is empty of inherent, independent existence. It is ungraspable but clearly presence-ing, appearing, as the most clear and vivid Presence itself. If you realise this Presence you cannot deny this because it is the luminosity of Buddha-Nature itself which is so clear, more real than real that you cannot have a doubt about it. There is no separation between you and what is perceived, so there is just THAT - the vividness of sound, the pain, the scenery. Yet when we try to locate it, and find an independent inherent existence of say a person, a self, or the 'redness' of a red flower, it cannot be found anywhere we look. It is just appearing but without substance, however this does not deny the presence, appearance, reality of the pain/suffering/etc.

I’m merely very confused, rather than holding an extreme view of non-existence per se. I’m trying to understand properly the various explanations of ‘like an illusion’ and ‘is an illusion’ from both Buddhist and non-Buddhist view-points.

Compassion is a natural response to perceiving someone elses pain. Because pain is arising and it is not an illusion -- it is the experiential reality of the other person, and action can be done to help the other person relatively speaking, but at the same time there is no need for an illusion that there is 'someone suffering' or 'someone who can save the person suffering'. There are just experiences without experiencer, action without doer, and all experiences are vivid but empty.

Yes, physical pain and suffering can be separated. I cannot say I am at that level, so I can quote something from a highly experienced monk Bhante Gunaratana to give you an idea:

http://www.vipassana.com/meditation/mindfulness_in_plain_english_12.php

That last part is more subtle. There are really no human words to describe this action precisely. The best way to get a handle on it is by analogy. Examine what you did to those tight muscles and transfer that same action over to the mental sphere; relax the mind in the same way that you relax the body. Buddhism recognizes that the body and mind are tightly linked. This is so true that many people will not see this as a two-step procedure. For them to relax the body is to relax the mind and vice versa. These people will experience the entire relaxation, mental and physical, as a single process. In any case, just let go completely till you awareness slows down past that barrier which you yourself erected. It was a gap, a sense of distance between self and others. It was a borderline between 'me' and 'the pain'. Dissolve that barrier, and separation vanishes. You slow down into that sea of surging sensation and you merge with the pain. You become the pain. You watch its ebb and flow and something surprising happens. It no longer hurts. Suffering is gone. Only the pain remains, an experience, nothing more. The 'me' who was being hurt has gone. The result is freedom from pain.

This is an incremental process. In the beginning, you can expect to succeed with small pains and be defeated by big ones. Like most of our skills, it grows with practice. The more you practice, the bigger the pain you can handle. Please understand fully. There is no masochism being advocated here. Self-mortification is not the point.

If compassion is a natural response, then why we do see and experience cruelty, apathy and indifference in ourselves and from fellow humans?

Why are there wars, torture chambers, rape and sexual slavery?

It sounds like profound, indirect masochism to me. Only that there may be an absence of intention to deliberately self-harm.

If everyone or at least a quarter of the world population succeeds in the above mental training, then theoretically speaking, the demand for painkillers, doctors and hospitals would decrease and eventually died out.

Furthermore, since this method sounds rather non-religious but yet highly effective in eliminating physical pain completely (it should in theory work for emotional pain as well), then what real motivation is there for aspiring Bodhisattvas to develop compassion and wisdom to that of a fully enlightened Buddha?

-

Originally posted by Spnw07:

Maybe you can substitute the word 'character' with 'actor'. If I'm an actor acting out an character who looks at another co-actor acting out a drowning character, I won't be so foolish as to be anxious to save him or her, unless it's part of the script. Safety procedures will definitely be in place (maybe divers are supporting that co-actor under the sea surface). This will also be the same if I'm acting out the drowning character.

If the setting is a mere swimming pool but merely flimed in such a way to appear like the sea, there's little need to raise a real alarm of danger, isn't it?

Anyway, this is just sharing my thoughts. Don't take it too literally and over-analyse too. =)

let's take this a little further while trying not to distort this analogy too much, though it'll break at some point i think :-)

the catch here is that this reality show that we're starring in has no safety procedures - everything we do has real-world consequence a.k.a workings of karma. the other catch is we are unaware that we are merely actors in this drama and thus we put in our real feelings and anguish into the drama.

the only other personal experience i can relate to is while we're in a dream. when someone insults me in a dream, i really get angry and retaliate. when i get into a disastrous accident in a dream, there is real feeling of panic. i invest my instinctive emotions into the dream because i'm unaware that it is merely a dream. i only realize its all a dream after waking up, but nevertheless, the emotions and anguish i experience in the dream are "real", as far as the dream lasts.

in fact, if you're sensitive enough, you can still experience the "real" emotions of anguish and panic of the dream lingering in your waking moments, shortly after you have waken. in that moment of awareness as you look at those dreamy emotions, they are still "real" because you can really feel it (eg. your heart still pounding from panic..etc) but at the same time you're also aware that it is all merely a dream so you're not genuinely panicking anymore. so in that sense, it is like an illusion because it is "real" as you can really feel the dream emotions, but "not real" as you are aware it is merely a dream.

hope it helps, and i didn't push the analogy too far.

-

Originally posted by Jamber:

let's take this a little further while trying not to distort this analogy too much, though it'll break at some point i think :-)

the catch here is that this reality show that we're starring in has no safety procedures - everything we do has real-world consequence a.k.a workings of karma. the other catch is we are unaware that we are merely actors in this drama and thus we put in our real feelings and anguish into the drama.

the only other personal experience i can relate to is while we're in a dream. when someone insults me in a dream, i really get angry and retaliate. when i get into a disastrous accident in a dream, there is real feeling of panic. i invest my instinctive emotions into the dream because i'm unaware that it is merely a dream. i only realize its all a dream after waking up, but nevertheless, the emotions and anguish i experience in the dream are "real", as far as the dream lasts.

in fact, if you're sensitive enough, you can still experience the "real" emotions of anguish and panic of the dream lingering in your waking moments, shortly after you have waken. in that moment of awareness as you look at those dreamy emotions, they are still "real" because you can really feel it (eg. your heart still pounding from panic..etc) but at the same time you're also aware that it is all merely a dream so you're not genuinely panicking anymore. so in that sense, it is like an illusion because it is "real" as you can really feel the dream emotions, but "not real" as you are aware it is merely a dream.

hope it helps, and i didn't push the analogy too far.

gravity still works even if you are an actor, right?. So shouldn't Karma be present even in a dream? Karma is not created, influenced or limited by human thoughts and feelings, time and space right?

What is a dream? What defines a dream? We can be talking about dreams we have while we are asleep or the abstract sense of the word.

So if I killed someone, do I tell myself I'm merely dreaming and I can 'wake up' without having to bear any negative consequences?

I feel the fear of having killed someone, I also feel the excitement. So do I tell myself that the feelings of fear and excitement aren't 'real' as I further remind myself I'm merely having a dream of feeling fearful and excited after killing someone in a dream?

-

Originally posted by Spnw07:

Is the true nature of Nirvana Samsara as well since it is one and not two?

David Loy:

"Nothing of sa�s�ra is different from nirv�ṇa, nothing of nirv�ṇa is different from sa�s�ra. That which is the limit of nirv�ṇa is also the limit of sa�s�ra; there is not the slightest difference between the two." [1] And yet there must be some difference between them, for otherwise no distinction would have been made and there would be no need for two words to describe the same state. So N�g�rjuna also distinguishes them: "That which, taken as causal or dependent, is the process of being born and passing on, is, taken noncausally and beyond all dependence, declared to be nirv�ṇa." [2] There is only one reality -- this world, right here -- but this world may be experienced in two different ways. Sa�s�ra is the "relative" world as usually experienced, in which "I" dualistically perceive "it" as a collection of objects which interact causally in space and time. Nirv�ṇa is the world as it is in itself, nondualistic in that it incorporates both subject and object into a whole which, M�dhyamika insists, cannot be characterized (Chandrakīrti: "Nirv�ṇa or Reality is that which is absolved of all thought-construction"), but which Yog�c�ra nevertheless sometimes calls "Mind" or "Buddhanature," and so forth"It sounds like profound, indirect masochism to me. Only that there may be an absence of intention to deliberately self-harm.

If everyone or at least a quarter of the world population succeeds in the above mental training, then theoretically speaking, the demand for painkillers, doctors and hospitals would decrease and eventually died out.

Furthermore, since this method sounds rather non-religious but yet highly effective in eliminating physical pain completely (it should in theory work for emotional pain as well), then what real motivation is there for aspiring Bodhisattvas to develop compassion and wisdom to that of a fully enlightened Buddha?

Well if it were that simple, then yes, perhaps, there would be much less need for painkillers, doctors and hospitals. But is it realistic that everyone can immediately reach Bhante Gunaratana's level of practice considering that Bhante Gunaratana actually started meditating since he was a kid and is already an old man now?

So realistically speaking I believe painkillers is still needed for most people. The next thing is, pain is usually a symptom of a deeper physical illness. If we simply ignore the pain and not address it from its roots by seeing a physician and getting a diagnosis, then we aren't doing well to take care of our body.

That said, there are many stories of miraculous healing through Vipassana meditation as described in many instances (scroll down to the bottom in http://www.buddhanet.net/budsas/ebud/ebmed006.htm for an example of having long term or terminal illnesses cured by simply practicing vipassana meditation), and my dharma teachers and master also attest to the healing power of practicing dharma.

Our moderator Thusness used to tell me many years ago so I can't remember the exact details, of how he used to displaced a bone or something and it was very painful, but he just keep sensing fully and practicing vipassana until it self healed and the next x ray showed that it completely healed by itself.

Anyway, Vipassana practice (i.e. insight meditation) in fact is only taught in Buddhism, and is the path to liberation.

-

Originally posted by An Eternal Now:

David Loy:

"Nothing of sa�s�ra is different from nirv�ṇa, nothing of nirv�ṇa is different from sa�s�ra. That which is the limit of nirv�ṇa is also the limit of sa�s�ra; there is not the slightest difference between the two." [1] And yet there must be some difference between them, for otherwise no distinction would have been made and there would be no need for two words to describe the same state. So N�g�rjuna also distinguishes them: "That which, taken as causal or dependent, is the process of being born and passing on, is, taken noncausally and beyond all dependence, declared to be nirv�ṇa." [2] There is only one reality -- this world, right here -- but this world may be experienced in two different ways. Sa�s�ra is the "relative" world as usually experienced, in which "I" dualistically perceive "it" as a collection of objects which interact causally in space and time. Nirv�ṇa is the world as it is in itself, nondualistic in that it incorporates both subject and object into a whole which, M�dhyamika insists, cannot be characterized (Chandrakīrti: "Nirv�ṇa or Reality is that which is absolved of all thought-construction"), but which Yog�c�ra nevertheless sometimes calls "Mind" or "Buddhanature," and so forth"If Nirvana cannot be characterised, how do we know it is a reality? Wouldn't samsara be the more real reality? What do you mean by samsara being a relative world? The above is quite deep for me.

Well if it were that simple, then yes, perhaps, there would be much less need for painkillers, doctors and hospitals. But is it realistic that everyone can immediately reach Bhante Gunaratana's level of practice considering that Bhante Gunaratana actually started meditating since he was a kid and is already an old man now?

So realistically speaking I believe painkillers is still needed for most people. The next thing is, pain is usually a symptom of a deeper physical illness. If we simply ignore the pain and not address it from its roots by seeing a physician and getting a diagnosis, then we aren't doing well to take care of our body.

That said, there are many stories of miraculous healing through Vipassana meditation as described in many instances (scroll down to the bottom in http://www.buddhanet.net/budsas/ebud/ebmed006.htm for an example of having long term or terminal illnesses cured by simply practicing vipassana meditation), and my dharma teachers and master also attest to the healing power of practicing dharma.

Our moderator Thusness used to tell me many years ago so I can't remember the exact details, of how he used to displaced a bone or something and it was very painful, but he just keep sensing fully and practicing vipassana until it self healed and the next x ray showed that it completely healed by itself.

Anyway, Vipassana practice (i.e. insight meditation) in fact is only taught in Buddhism, and is the path to liberation.

However, time is not necessarily a guarantee (many other conditions are involved) that one would naturally advance like Bhante. He must have practised very well in his previous rebirths, so that in this lifetime, it appears that he achieved this stage because he started early from childhood.

Although Vipassana practice is only taught in Buddhism, not many would know what really constitutes vipassana practice as taught by the Buddha.

Since those who are liberated usually keep silent or have already passed away into blissful rebirths, it's anyone's guess as to whether one is really liberated by following what appears or is spread by word or mouth as vipassana practice.

Theoretically speaking, if we take care of our mind through the mental training you have described, we should be able to eliminate any root cause of our physical illness, isn't it? Then taking good care of our mind would be the same as taking good care of our body?

And you haven't answered this part of my earlier post:

If compassion is a natural response to perceiving someone else's pain, then why we do see and experience cruelty, apathy and indifference in ourselves and from fellow humans?

Why are there wars, torture chambers, rape and sexual slavery?

-

Illnesses that cannot be cured by doctors, such as that which Thusness encountered, and others like my Taiwanese teacher who also encountered an injury that his friends and doctors all thought will leave him paralysed for life yet he miraculously healed himself through dharma practice within 1-2 weeks are examples of the miraculous healing power of dharma if practiced well. However I am not sure if this will happen every time and I suppose sometimes, if the bad karma is really strong one still cannot avoid certain amount of suffering, as even the Buddha and his Arhat disciples are known to get sick at times.

Actually, the instructions taught by Buddha are laid out very well in the suttas, for example the Mahasatipatthana Sutta is so precise and detailed on the practice of Vipassana as to go into every single details on how one is to be mindful of each minutest details of our sensate reality so as to realise its true nature, and that such a practice is able to result in realisation and liberation in a period of 7 days to 7 years of practice (serious practice of course). Many people have practiced this today and continue to attain liberation or at least gain a high degree of insight, which testifies to the success and relevance of such a practice to people even in the modern world.

The Buddha said that when he is no longer around, then let the Dhamma be the guide. In this case, suttas like Mahasatipatthana Sutta and other suttas comes in handy for sincere practitioners. And of course, the Sangha (the enlightened beings in the sangha) as well, can be a valuable source of guidance and experience for other practitioners.

Why do I say compassion is natural? As a matter of fact it motivates everything we do in life, unfortunately it is twisted by the ego into the three poisons.* If you are suffering, do you want to end the suffering? Of course, and you'll do something about it and the response is natural. However because we have a false division of subject and object, me and others, our concern is on the 'me' instead of others. We become concerned about our own well-being than others because of our narrow scope and fixation on the 'me' and 'mine'. If we do not divide into 'me' and 'others', if we let go of self-fixation and expand our awareness, then our compassion becomes more natural and spontaneous. When suffering happens, compassionate action to end suffering will happen and there is no self-centeredness that will hold you back.

*Dharma Dan:

As stated earlier, a helpful concept here is compassion, a heart aspect of the practice and reality related to kindness. You see, wherever there is desire there is suffering, and wherever there is suffering there is compassion, the desire for the end of suffering. You can actually experience this. So obviously there is some really close relationship between suffering, desire and compassion. This is heavy but good stuff and worth investigating.We might conceive of this as compassion having gotten caught in a loop, the loop of the illusion of duality. This is sort of like a dog’s tail chasing itself. Pain and pleasure, suffering and satisfaction always seem to be “over there.” Thus, when pleasant sensations arise, there is a constant, compassionate, deluded attempt to get over there to the other side of the imagined split. This is fundamental attraction. You would think that we would just stop imagining there is a split, but somehow that is not what happens. We keep perpetuating the sense of a split even as we try to bridge it, and so we suffer. When unpleasant sensations arise, there is an attempt to get away from over there, to widen the imagined split. This will never work, because it doesn’t actually exist, but the way we hold our minds as we try to get away from that side is painful. When boring or unpleasant sensations arise, there is the attempt to tune out all together and forget the whole thing, to try to pretend that the sensations on the other side of the split are not there. This is fundamental ignorance and it perpetuates the process, as it is by ignoring aspects of our sensate reality that the illusion of a split is created in the first place.These strict definitions of fundamental attraction, aversion and ignorance are very important, particularly for when I discuss the various models of the stages of enlightenment. Given the illusion, it seems that somehow these mental reactions will help in a way that will be permanent. Remember that the only thing that will fundamentally help is to understand the Three Characteristics to the degree that makes the difference, and the Three Characteristics are manifesting right here.Remember how it was stated above that suffering motivates everything we do? We could also say that everything we do is motivated by compassion, which is part of the fundamentally empty nature of reality. That doesn’t mean that everything we do is skillful; that is a whole different issue.Compassion is a very good thing, especially when it involves one's self and all beings. It is sort of the flip side of the Second Noble Truth. The whole problem is that “misdirected” compassion, compassion that is filtered through the process of ego and its related habits, can produce enormous suffering and often does. It is easy to think of many examples of people searching for happiness in the strangest of places and by doing the strangest of things. Just pick up any newspaper. The take-home message is to search for happiness where you are actually likely to find it.We might say that compassion is the ultimate aspect of desire, or think of compassion and desire on a continuum. The more wisdom or understanding of interconnectedness there is behind our intentions and actions, the more they reflect compassion and the more the results will turn out well. The more greed, hatred and delusion or lack of understanding of interconnectedness there is behind our intentions and actions, the more they reflect desire and the more suffering there will likely be.This is sometimes referred to as the “Law of Karma,” where karma is a word that has to do with our intentions and actions. Some people can get all caught up in specifics of this that cannot possibly be known, like speculating that if we kill a bug we will come back as a bug and be squished. Don't. Cause and effect, also called interdependence, is just too imponderably complex. Just use this general concept to look honestly at what you want, why, and precisely how you know this. Examine what the consequences of what you do and think might be for yourself and everyone, and then take responsibility for those consequences. It's a tall order and an important practice to engage in, but don't get too obsessive about it. Remember the simplicity of the first training, training in kindness, generosity, honesty and clarity, and gain balance and wisdom from the other two trainings as you go. -

Originally posted by An Eternal Now:

Illnesses that cannot be cured by doctors, such as that which Thusness encountered, and others like my Taiwanese teacher who also encountered an injury that his friends and doctors all thought will leave him paralysed for life yet he miraculously healed himself through dharma practice within 1-2 weeks are examples of the miraculous healing power of dharma if practiced well. However I am not sure if this will happen every time and I suppose sometimes, if the bad karma is really strong one still cannot avoid certain amount of suffering, as even the Buddha and his Arhat disciples are known to get sick at times.

The tough part is in knowing clearing when to accept that one's bad karma is really strong. For some, paralysis within 1-2 weeks can be considered strong bad karma. But if one gets cured like your Taiwanese teachr, then you would think you might be foolish for thinking it is strong bad karma.

So the paradox or irony (correct my vocaubulary if you like) is, if it's really bad, you can't avoid suffering. And you can never know whether this unavoidable certain amount of suffering is actually the original, full amount of suffering that ripens for your bad karma.

So you can console yourself either foolishly that my karma has been reduced, but without insight knowledge of the actual, full impact of your bad karma, how do you compare and know whether your effects and duration of your strong bad karma has been reduced?

Only the Buddha and his Arhat disciples can make an accurate and non-biased comparison as to the extent of their suffering for any ripened or soon-to-ripen strong bad karma.

Actually, the instructions taught by Buddha are laid out very well in the suttas, for example the Mahasatipatthana Sutta is so precise and detailed on the practice of Vipassana as to go into every single details on how one is to be mindful of each minutest details of our sensate reality so as to realise its true nature, and that such a practice is able to result in realisation and liberation in a period of 7 days to 7 years of practice (serious practice of course). Many people have practiced this today and continue to attain liberation or at least gain a high degree of insight, which testifies to the success and relevance of such a practice to people even in the modern world.

The Buddha said that when he is no longer around, then let the Dhamma be the guide. In this case, suttas like Mahasatipatthana Sutta and other suttas comes in handy for sincere practitioners. And of course, the Sangha (the enlightened beings in the sangha) as well, can be a valuable source of guidance and experience for other practitioners.

Then it is quite sad that this sutta is not widely published and distributed enough to beginner Buddhists through temples or affliliated organisations. Since this sutta is so precise, detailed and clearly beneficial even within short time span, then more talks should be held not only to promote awareness, but to clear doubts and help plant seeds of motivation for serious practice among Buddhists. I mean such a good sutta should not only be confined to meditation classes in temples or any Buddhist organisation.

Why do I say compassion is natural? As a matter of fact it motivates everything we do in life.* If you are suffering, do you want to end the suffering? Of course, and you'll do something about it and the response is natural. However because we have a false division of subject and object, me and others, our concern is on the 'me' instead of others. We become concerned about our own well-being than others because of our narrow scope and fixation on the 'me' and 'mine'. If we do not divide into 'me' and 'others', if we let go of self-fixation and expand our awareness, then our compassion becomes more natural and spontaneous. When suffering happens, compassionate action to end suffering will happen and there is no self-centeredness that will hold you back.

*Dharma Dan: