Iapetus

-

Iapetus (eye-ap'-ə-təs, IPA /aɪˈæpətəs/, Greek Ιαπετός

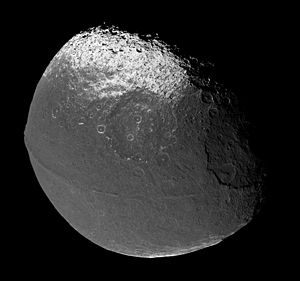

is the third-largest moon of Saturn, discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1671. Iapetus is best known for its dramatic 'two-tone' coloration, but recent discoveries by the Cassini mission have revealed several other unusual physical characteristics. These mysteries are currently under investigation by scientists and new information about Iapetus is accumulating continuously.

is the third-largest moon of Saturn, discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1671. Iapetus is best known for its dramatic 'two-tone' coloration, but recent discoveries by the Cassini mission have revealed several other unusual physical characteristics. These mysteries are currently under investigation by scientists and new information about Iapetus is accumulating continuously.

Iapetus is named after the mythological Iapetus. It is also designated Saturn VIII.

Giovanni Cassini named the four moons he discovered (Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus) Lodicea Sidera ("the stars of Louis") to honour king Louis XIV. However, astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and Titan as Saturn I through Saturn V. Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered, in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended to Saturn VII.

The names of all seven satellites of Saturn then known come from John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of Mimas and Enceladus) in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope ([2]), wherein he suggested the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Cronos (the Greek Saturn), be used.

The orbit of Iapetus is somewhat unusual. Although it is one of Saturn's largest moons, it orbits much farther from Saturn than the next closest major moon, Titan. It has also the most inclined orbital plane of the regular satellites; only the irregular outer satellites like Phoebe have more inclined orbits. The cause of this is unknown.

Because of this distant, inclined orbit, Iapetus is the only large moon from which the rings of Saturn would be clearly visible; from the other inner moons, the rings would be edge-on and difficult to see.

The low density of Iapetus indicates that it is primarily composed of ice, with only a small amount of rocky materials.

Furthermore, the overall shape of Iapetus is neither spherical nor ellipsoid—unusual for a large moon; parts of its globe appear to be squashed flat, and its unique equatorial ridge (see below) is so high that it visibly distorts the moon's shape even when viewed from a distance. Scientists are currently unable to describe Iapetus's shape perfectly as the Cassini probe has not yet imaged its entire surface. [3]

Iapetus is a heavily cratered body, and Cassini images have revealed large impact basins in the dark region, at least three of which are over 350 km wide. The largest has a diameter over 500 km; its rim is extremely steep and includes a scarp over 15 km high.

[edit]

Two-tone coloration

In the seventeenth century, Giovanni Cassini observed that he could see Iapetus only on one side of Saturn and not on the other. He drew the conclusion that one side of Iapetus was darker than the other, a conclusion confirmed by images from the Voyager and Cassini spacecraft.

The difference in colouring between the two Iapetian hemispheres is striking. The leading hemisphere is dark (albedo .03–.05) with a slight reddish-brown coloring, while most of the trailing hemisphere and poles is bright (albedo .5-.6, almost as bright as Europa). The pattern of coloration is analogous to a spherical yin-yang symbol. The dark region is named Cassini Regio, and the bright region Roncevaux Terra.

The origin of this dark material is not currently known, though several theories have been proposed (see below). Its thickness is also unknown; there are no bright craters present on the dark hemisphere, so if the dark material is thin it must either be extremely recent, or constantly renewed, as otherwise a meteor impact would have punched through the layer to reveal brighter underlying material.

When NASA's Voyager 2 flew past Iapetus on August 22, 1981 at a relatively distant 966,000 km (600,000 mi), the spacecraft's cameras could make out few details in the area of dark material, but revealed the bright side to be icy and heavily cratered. On December 31, 2004, the Cassini spacecraft passed within 123,000 km (77,000 mi) of Iapetus and photographed Cassini Regio at far a higher resolution than Voyager was able, but the mystery surrounding its origin has only deepened.

Cassini is scheduled for a much closer approach on September 10, 2007 — 1,200 km (800 mi). -

Sources from space

Close-up of northern pole.The dark material might be formed of organic compounds similar to the substances found in primitive meteorites or on the surfaces of comets; Earth-based observations have shown it to be carbonaceous and it probably includes cyano-compounds such as frozen hydrogen cyanide polymers.

There have also been suggestions that the dark material originated from other Saturnian moons. For example, it was long suspected that the material may have spiralled in from Phoebe, having been knocked free from the smaller moon's surface by micrometeor impacts and then swept up by Iapetus' leading hemisphere. However, despite being widely cited, this theory is no longer tenable: observations have shown Phoebe's surface to have a different color to that of the dark material of Iapetus (indeed in 2005 it was announced that Phoebe's composition is closer to the bright Iapetian hemisphere than the dark one).

Another suggestion has been than Iapetus became coated by dark material created in the aftermath of the destruction of the object which went on to become Hyperion, whose shape is consistent with its formation in a violent impact. However, there remain doubts as to whether or not such an event can produce a stream of debris able to produce the distribution of dark material seen on Iapetus.

[edit]

Internal sources

It is possible that the dark material may have originated from some internal source, perhaps brought to the surface by a combination of meteor impact and cryovolcanism. This theory is supported by the apparent concentration of the material on crater floors. It has been suggested that since Iapetus is far from Saturn and would have avoided much of the heating its other moons received during the formation of the Solar system, Iapetus may have retained methane or ammonia ice in its interior that later erupted to the surface as cryovolcanic lava and was then blackened by solar radiation, charged particles, and cosmic rays. A dark ring of material about 100 kilometers in diameter straddling the border between the leading and trailing hemispheres of Iapetus is suggestive of such vulcanism, resembling structures that have formed on the Moon and on Mars as a result of volcanic material flowing into impact craters with a central peak.

Photomosaic of Cassini images taken Dec. 31, 2004, showing the dark Cassini Regio, large craters, and the newly discovered equatorial ridgeAn alternative internal source may be the evaporation of water ice. Due to its slow rotation, Iapetus has the warmest surface in the Saturnian system (130 K in the dark region) allowing the sublimation of water ice on the surface. After sublimation, the water then freezes back to the surface and re-heats until it reaches a location where it is no longer able to sublimate. The dark areas may be the result of such a process, since the material there lacks water. However, this hypothesis fails to explain why only one hemisphere is dark.

The equatorial ridge

A further mystery was discovered when the Cassini spacecraft imaged Iapetus on December 31, 2004, and revealed an equatorial ridge about 20 km wide and 13 km high extending 1300 km through the center of Cassini Regio [4]. Parts of the ridge rise more than 20 km over the surrounding plains. The ridge follows the moon's equator almost perfectly and is confined to Cassini Regio. Some bright mountains near the boundary of Cassini Regio that apparently belong to this ridge were seen in Voyager photos; however, the Voyagers were unable to make out any details in the dark region itself, so the extent of the ridge is only now apparent. The ridge system is heavily cratered indicating that it is ancient.[5]

The images are currently being analyzed by scientists and no firm conclusions have yet been announced about the ridge's origin. At least three hypotheses are in circulation.

One possibility is that the ridge is a remnant of the oblate shape of the young Iapetus, when it was rotating more rapidly than it does today.[6] The height of the ridge suggests a maximum rotational period of 17 hours. In order for Iapetus to have cooled quickly enough to preserve the ridge, but remain plastic long enough for the tides raised by Saturn to have slowed the rotation to its current tidally locked 79 days, Iapetus could only have been heated by the radioactive decay of aluminium-26. This isotope appears to have been abundant in the solar nebula from which Saturn formed, but has since all decayed. The quantities of Al26 needed to heat Iapetus to the required temperature give a tentative date to its formation relative to the rest of the Solar system: Iapetus must have come together earlier than expected, only two million years after the asteroids started to form.

Another possibility is that the ridge is icy material that has welled up from beneath the surface and then solidified. However, this does not explain why the ridge follows the equator.

A third possibility has been suggested by Paulo C.C. Freire of Arecibo Observatory, who proposes that the ridge and Cassini Regio were created when Iapetus grazed the outer edges of Saturn's rings in the distant past. However, Freire's theory requires Iapetus to have been later ejected to its current, distant orbit around Saturn. [7]

[edit]

See also

List of geological features on Iapetus

[edit]

Speculation that Iapetus is artificial

The oddness of Iapetus has occasionally led to speculation that it may be an artificial construction by extraterrestrials. In 1980, Donald Goldsmith and Tobias Owen suggested that the striking bicoloration of Iapetus might be the result of alien modification of a natural object.

In 2005, Richard C. Hoagland speculated that Iapetus might be a fully or partially artificially constructed world by an ancient (and likely long-gone) extraterrestrial civilization. His thesis relies on the moon's arguably angular shape (unusual in a moon of Iapetus's size, which ought to be compressed into an approximately spherical or ellipsoid form under pressures generated by its own gravity), the equatorial ridge, and a close examination of surface features. [8]

The scientific mainstream considers such ideas fanciful at best. -

wat could have cause a ridge on the equator of tat moon?

-

Something hit it lor. But I wonder what thing got such big impact. Even if it's impact, it will be a crater.

-

Looks so crap. I dont wana live there